Ball Python Care Guide

Python regius

Natural History

The IUCN Red List assesses the conservation status of species, ranging from Least Concern (LC) to Extinct (EX). Ball pythons (Python regius) are classified as Least Concern due to their wide distribution and stable wild populations. However, habitat loss and collection for the pet trade pose threats, though captive breeding has reduced pressure on wild populations.

Ball pythons are one of the most beloved reptiles in captivity, known for their docile temperament, manageable size, and stunning array of morphs. To provide the best care, it’s crucial to understand both their natural history and specific needs.

Ball Pythons are members of the Pythonidae family of snakes, containing approximately 40 recognized species (Pyron et al., 2011; Reynolds et al., 2014). These species are primarily distributed across Africa, Asia, and Australia, with a few species found in Papua New Guinea and surrounding islands. Fossil evidence (Head and Holroyd, 2014) shows that pythons originated in the Late Cretaceous period, roughly 65 million years ago, during the final stages of the age of dinosaurs. Molecular evidence (Rawlings et al., 2008) shows that Ball Pythons diverged as a distinct species approximately 10–20 million years ago. Interestingly, their closest living relatives are the Blood Pythons of Southeast Asia and the Indian and Burmese Pythons of Asia (Baker et al., 2015). The evolution of Ball Pythons is closely linked to the ecological expansion of grasslands and burrow ecosystems in Africa, driven by climatic shifts in the Miocene epoch. They evolved a smaller body size compared to their relatives to better utilize burrow microhabitats, allowing them to escape predators and reduce interspecies competition (Shine and Slip, 1990; Rawlings et al., 2008). They are found in grasslands, savannas, and open forests, often near water. However, they are primarily fossorial, meaning they live underground most of the time.

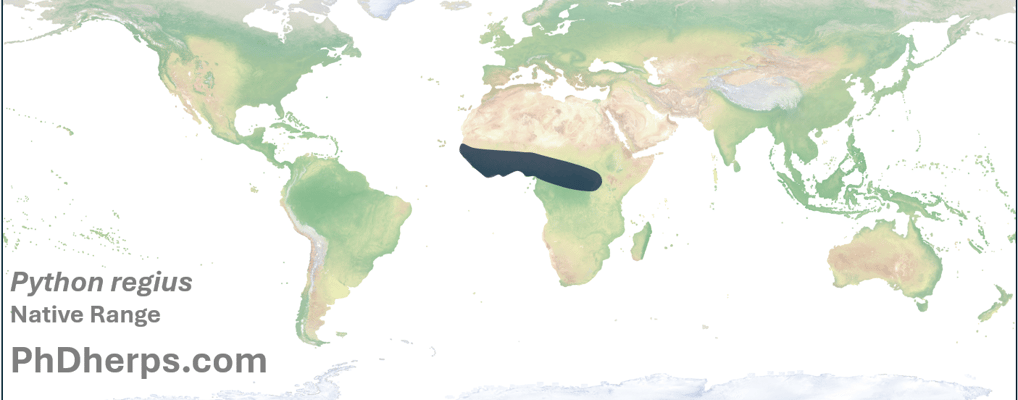

The Ball Python (Python regius) is native to Sub-Saharan Africa, specifically West and Central Africa. The species was first described scientifically by François Marie Daudin, a French zoologist, in 1803, who provided the most detailed early description of the species in his Histoire naturelle des reptiles. However, the name "Boa regia" was first used by George Shaw in 1802, though this name is no longer valid under modern taxonomic conventions. The currently accepted name, Python regius, reflects its inclusion in the Python genus and its regal association. The second half (called the specific epithet) of their currently accepted scientific name, "regius," is Latin for "royal," reflecting their use by African royalty as ornamental animals, earning their second common name, the Royal Python. Today, their more well-known common name, "Ball Python," derives from their stereotypical defensive behavior, where they coil into a ball with their head covered by multiple body loops.

Supporting Literature for Ball Pythons

Captive Care and Husbandry

What to do before you get a Ball Python:

Before purchasing a ball python, research and preparation are crucial. Learn about their natural behaviors, and understand that they can live for 20–30 years, requiring a long-term commitment. Have an enclosure ready before bringing one home. Ensure proper temperature and humidity with reliable thermostats and hygrometers to create a stable, stress-free environment. Buy from a reputable breeder who can provide health records and feeding schedules. Opt for captive-bred snakes, as they are healthier and less stressed than wild-caught ones. Quarantine new snakes for at least 30 days if you already own other reptiles. Give your new ball python a week to acclimate before handling or feeding, and provide hiding spots to help it feel secure.

Housing Options:

Ball pythons can thrive in various types of enclosures, each with its pros and cons. Snake racks, consisting of stacked bins within a shelving system, are a popular choice for breeders and keepers with multiple snakes, offering efficient use of space, excellent humidity retention, and ease of maintenance, though they lack visibility and enrichment opportunities. Rubbermaid tubs are another cost-effective option, often used in racks or independently, and are excellent for humidity control but less visually appealing. Glass terrariums allow for easy observation and are widely available, though they can struggle to maintain humidity unless modified. PVC enclosures are durable, lightweight, and well-insulated, making them ideal for long-term use, especially for adult ball pythons, though they come with a higher upfront cost. Lastly, wooden vivariums are a common DIY option, though they require sealing and regular maintenance. For keepers seeking a naturalistic setup, bioactive enclosures provide enrichment with live plants and a cleanup crew, offering unmatched aesthetics and sustainability but requiring more effort. Each enclosure type caters to different needs, so the best choice depends on your budget, experience, and goals as a keeper. For an expanded discussion of housing options, see our "Caging Options" page under our "Reptile Care Insights" tab.

Cage Sizes:

Ball pythons require appropriately sized enclosures as they grow to ensure they feel secure and have enough space to explore. We do not recommend large enclosures for small Ball Pythons. We find that in general, large enclosures overly stress the snake and causes more harm than good. Here are the recommended enclosure sizes based on their life stages:

For hatchling Ball Pythons, we suggest a 10-gallon (20 x 10 x 12 inches) or 20-gallon long terrarium (30 x 12 x 12 inches). Juvenile Ball Pythons can live comfortably in 20-gallon long terrariums and if comfortable, can be upgraded to a 40-gallon terrarium (36 x 18 x 16 inches). While a 40-gallon aquarium can function for adult Ball Pythons, we suggest PVC enclosures for adults (48 x 24 x 24 inches). Overall, we suggest PVC enclosures over terrariums due to their more enclosed nature, making the animal feel more comfortable and secure. These dimensions are meant to serve as a starting point. Each animal is unique in what they are comfortable with. In our experience, Ball Pythons habituate and eat more reliably in smaller enclosures. However, larger enclosures are also likely to be fine but significant hiding opportunities, microclimates, and shaded cave structures can help alleviate the stress of a larger enclosure while reducing the costs associated with purchasing multiple enclosures as your animal grows.

Substrate:

Ball Pythons are often found underground, so for keepers with only a few animals in terrariums, we suggest thick layers of substrate (2–4 inches in depth). The best option for cleanliness and humidity control is coconut husk. Coconut coir can also be used, but this can result in a dirtier-looking enclosure. It is harmless to the animals but many keepers don't like the "messy" look. Pure cypress mulch is another excellent choice, especially for its price, but be absolutely sure the mulch is not mixed with other woods. Aspen bedding is safe for Ball Pythons, but we do not recommend this option due to its inability to retain moisture without molding. For those looking to create a bioactive setup, a substrate mix of coconut coir, organic topsoil (free of additives), and sphagnum moss can provide an enriching and functional base for live plants and microfauna. We never suggest the use of cedar or pine for any reptile (with rare exceptions). Regardless of the substrate type, regular spot-cleaning and full substrate changes every 1–3 months (depending on enclosure conditions) are essential to maintain cleanliness and prevent bacterial growth.

Temperature and Humidity:

The key to successfully caring for a ball python is providing a temperature gradient, not a single uniform temperature throughout the enclosure. In the wild, snakes naturally move between different thermal environments to regulate their body temperature. Ball pythons need a "hot side" in their enclosure maintained at 88–91°F (31–33°C), with an area large enough for their entire body to access this temperature. Equally important is the "cool side," which should be kept between 75–80°F (24–27°C). For our animals, we maintain the hot side at 90°F and let the cool side stabilize at room temperature, which is often around 70°F. Over time, we observe their behavior and make individual adjustments. If a snake spends all its time on the warm side, we raise the overall gradient to encourage exploration. Conversely, if they only stay on the cool side, we lower the hot spot to ensure their comfort. For heat sources, I prefer heat pads over heat lights, but both can work effectively. Whichever option you choose, it is essential to connect all heat sources to a thermostat to prevent overheating. Never use heat sources without a thermostat, as this poses a significant risk to your snake’s health and safety.

Humidity, the measure of water content in the air, is another critical factor. Ball pythons require a relative humidity of 50–60%, with occasional fluctuations being natural and not cause for concern. Their native African environment is not constantly regulated, and similarly, their enclosure doesn’t need perfect consistency. The key is ensuring some areas of the enclosure always remain moist without becoming waterlogged. We achieve this by placing sphagnum moss under a hide and checking its moisture weekly. As long as the moss retains some dampness, your ball python will have access to a high-humidity microclimate. Measuring humidity can be tricky, as readings vary depending on placement and equipment. For accurate results, avoid placing hygrometers near the top of the enclosure, where the snake rarely resides. Instead, position one near the substrate on both the hot and cool sides of the enclosure. This method provides a more accurate picture of the environment your snake actually experiences.

Lighting:

As nocturnal animals, ball pythons do not require UVB lighting, but maintaining a day-night cycle using ambient or low-intensity LED lights is beneficial. We personally prefer ambient lighting, as the high-intensity lights available today often do not serve the needs of the animal. In fact, brightly illuminating a ball python’s enclosure is more for the keeper’s benefit and can cause unnecessary stress for the snake. If you choose to include a light in the enclosure, ensure it is dim and unobtrusive, and set it on a timed cycle that mimics the natural day-night rhythm of their native environment.

Diet and Feeding:

For as popular and abundant as ball pythons are, there is remarkably little data on their natural diet. The most comprehensive study comes from Luiselli and Angelici (1998), who analyzed their dietary habits in the wild. Ball python diets vary according to their size, age, and sex. Juvenile ball pythons, particularly those under 70 cm in length, primarily prey on small birds, while adults over 100 cm predominantly consume small mammals. Males exhibit more arboreal tendencies and often hunt birds, while females are predominantly terrestrial, focusing on mammalian prey. Common mammalian prey includes various rodent species such as Gambian pouched rats, black rats, rufous-nosed rats, shaggy rats, and striped grass mice.

For captive ball pythons, they are often fed an exclusive diet of rodents. Common rodent options include the house mouse (Mus musculus), Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus), and African soft-furred rat (Mastomys natalensis). Strong opinions exist within the reptile community regarding which prey is best. However, based on our experience, there is limited evidence to support many of these claims. Be cautious when receiving advice from those who "swear by" a particular method while dismissing others. Of the three common prey sources, we advise against using African soft-furred rats. While they may be convenient, they are known carriers of diseases, are illegal to possess in many states, and are listed as Injurious Wildlife under the Federal Lacey Act. Despite these restrictions, some individuals continue to possess and sell them illegally.

We suggest starting hatchling ball pythons on hopper mice and increasing the size of the prey as the snake grows. There are no strict rules for prey size, but a good guideline is to offer food approximately the same width as the snake's body. After they consume their prey, you should see a noticeable lump in their belly. If there is no lump, the prey is too small, and you should increase its size at the next feeding. As ball pythons grow, you can transition them to Norway rats for the remainder of their lives. Generally, the largest prey taken by ball pythons are medium-sized Norway rats (~150–200 grams).

We are strong proponents of feeding frozen-thawed rodents rather than live prey. In our collection of 300+ snakes, approximately 10% require live prey due to their refusal to eat pre-killed food. However, whenever possible, frozen-thawed prey should be used. This reduces unnecessary pain and suffering for the prey and minimizes risks to the snake, such as injury or stress. Hatchling snakes should be fed every 5–7 days. As they grow, feeding frequency should decrease until adulthood. For adults, we recommend feeding every 2–4 weeks based on the snake's individual needs, which we monitor by tracking their weights and behaviors.

Water:

Provide a water dish large enough for your Ball Python to soak in if desired. Snakes are strong swimmers so depth is not an issue as long as they can readily crawl out from the dish. Place the dish on the cool side of the enclosure to minimize evaporation and maintain proper humidity. Clean and refill the dish regularly with fresh, dechlorinated water, and immediately clean it if the snake defecates in it. If you see excessive soaking behavior, this may indicate stress, mites, or overheating.

Hides and Structures:

From our experience, this is an often overlooked need for all animals. Take a moment and think about their experience. While we see a captive and secure environment, they are looking for predators, worrying about being exposed, and constantly trying to avoid detection. Including plants, limbs, and other objects in a ball python's enclosure can provide enrichment and mimic their natural environment while reducing stress. Sturdy climbing branches or cork bark can encourage exploration and allow the snake to stretch and exercise. Live or artificial plants add visual appeal and can offer additional cover, helping the snake feel secure. Ensure all items are securely positioned to prevent tipping or injury, and use materials that are easy to clean and reptile-safe. For bioactive setups, live plants also help maintain humidity and create a more naturalistic habitat.

Handling and Health Checks:

When handling a ball python, approach it calmly and confidently from the side, avoiding sudden movements or reaching over its head to minimize stress. Always support its body fully, allowing the snake to feel secure while gently guiding its movement. Handle your ball python for short sessions (5–10 minutes) a few times a week to build trust and avoid overhandling, which can stress the snake. Avoid handling during shedding or within 48 hours after feeding, as these are times when the snake is more sensitive or prone to regurgitation. If the snake shows signs of stress, such as rapid tongue flicking, hissing, or balling up, return it to its enclosure to let it relax.

While handling your ball python, perform a quick health check by inspecting its body for signs of illness or injury. Look for clear eyes, smooth scales, and a clean vent area free of swelling or discharge. Check for retained shed, especially around the eyes (retained eye caps) and tail tip, which can lead to complications. Feel gently along the snake’s body for unusual lumps, bumps, or softness, which could indicate underlying issues. Observe its behavior for signs of respiratory distress, such as wheezing or open-mouth breathing, and ensure its mouth is free of lesions or excess mucus, which might suggest mouth rot. Regular checks like this help you catch potential health problems early.

Scientific Literature:

Baker, J., Mehta, R. S., & Venom Evolution Group. (2015). Systematics and evolutionary history of pythons: Molecular and morphological perspectives. Herpetology Notes, 8, 123–145.

Head, J. J., & Holroyd, P. A. (2014). Fossil snakes and the evolution of Pythonidae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 172(3), 651–672. https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12188

Luiselli, L., & Angelici, F. M. (1998). Sexual size dimorphism and natural history traits are correlated with intersexual dietary divergence in royal pythons (Python regius) from the rainforests of southeastern Nigeria. Italian Journal of Zoology, 65(2), 183–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/11250009809386810

Pyron, R. A., Burbrink, F. T., Colli, G. R., de Oca, A. N. M., Vitt, L. J., Kuczynski, C. A., et al. (2011). The phylogeny of advanced snakes (Colubroidea), with discovery of a new subfamily and comparison of support methods for likelihood trees. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 58(2), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.006

Rawlings, L. H., Barker, D. G., & Donnellan, S. C. (2008). Python phylogenetics: Inference from morphology and mitochondrial DNA. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 93(3), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2007.00904.x

Reynolds, R. G., Niemiller, M. L., & Revell, L. J. (2014). Toward a Tree-of-Life for the boas and pythons: Multilocus species-level phylogeny with unprecedented taxon sampling. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 71, 201–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2013.11.011

Shine, R., & Slip, D. J. (1990). Biological aspects of the adaptive radiation of Australasian pythons (Serpentes: Boidae). Herpetologica, 46(3), 283–290.

Popular Care Guides:

Brown, L. (2017). Ball Python Care: The complete guide to caring for and keeping ball pythons as pets. SRP Publishing.

De Vosjoli, P., Klingenberg, R., Barker, D., & Barker, T. (1994). The Ball Python Manual. Advanced Vivarium Systems.

De Vosjoli, P. (2005). Ball Pythons: A complete guide to Python regius. Advanced Vivarium Systems.

Judd, T. (2024). A new keeper's guide to ball pythons. Beginner Herp Guides.

McCurley, K. (2005). The Complete Ball Python: A comprehensive guide to care, breeding, and genetic mutations. New England Herpetoculture.

McCurley, K. (2006). Ball Pythons in Captivity. New England Herpetoculture.

McCurley, K. (2023). The Ultimate Ball Python: A comprehensive guide to care, breeding, and genetic mutations. New England Herpetoculture.

Purser, P. (2006). The Ball Python: Herpetocultural library. TFH Publications.

The care guide for ball pythons is incredibly informative! It helped me understand their habitat needs and common issues. Highly recommend for new snake owners!

Alex Smith

★★★★★

Contact Us for Ball Python Care

Reach out for expert advice on ball python care.